Han de ir por todos los fines de la tierra, a la mano derecha, y a la mano izquierda, y de todo en todo irán hasta la ribera del mar, y pasarán adelante.

[They shall go unto the ends of the earth, to the right and to the left, and in the end they will reach the seashore, and still they shall go onward.]

--Relación de Michoacán, ca. 1540

My paternal great-grandparents, who were legal U.S. residents, emigrated back to their native México during the Great Depression. Their son, my Abuelo who was born in San Antonio, became a U.S. immigrant to México at seventeen. Time passed and fate would again intervene when my father, a chronic asthmatic learned of a place where he could live a healthier and perhaps happier life. Not able to secure “papers” quick enough, he made the journey north to Phoenix, Arizona, undocumented. Two years later he sent for my mother and eight children. I was eleven years old when I became an illegal immigrant.

The train from México City to Nogales, was filled with both excitement and fear. The car ride to Phoenix was a surreal dream as a mirage of water appeared on the sun-drenched road. Phoenix was nothing like the city I grew up in. The two-room shared trailer was a far cry from the home we left behind. My father was no longer a professional, but now a laborer while my mother handcrafted many things to help bring in some extra income. I remember my mother’s tears and the years it took for them to finally dry up.

My personal story is the starting point behind this body of work. This series focuses on immigration, specifically in the Southwest, and on complex issues such as the journey, the landscape, the gains and losses of people who continue to travel north from Latin America to the U.S. in search of a better life.

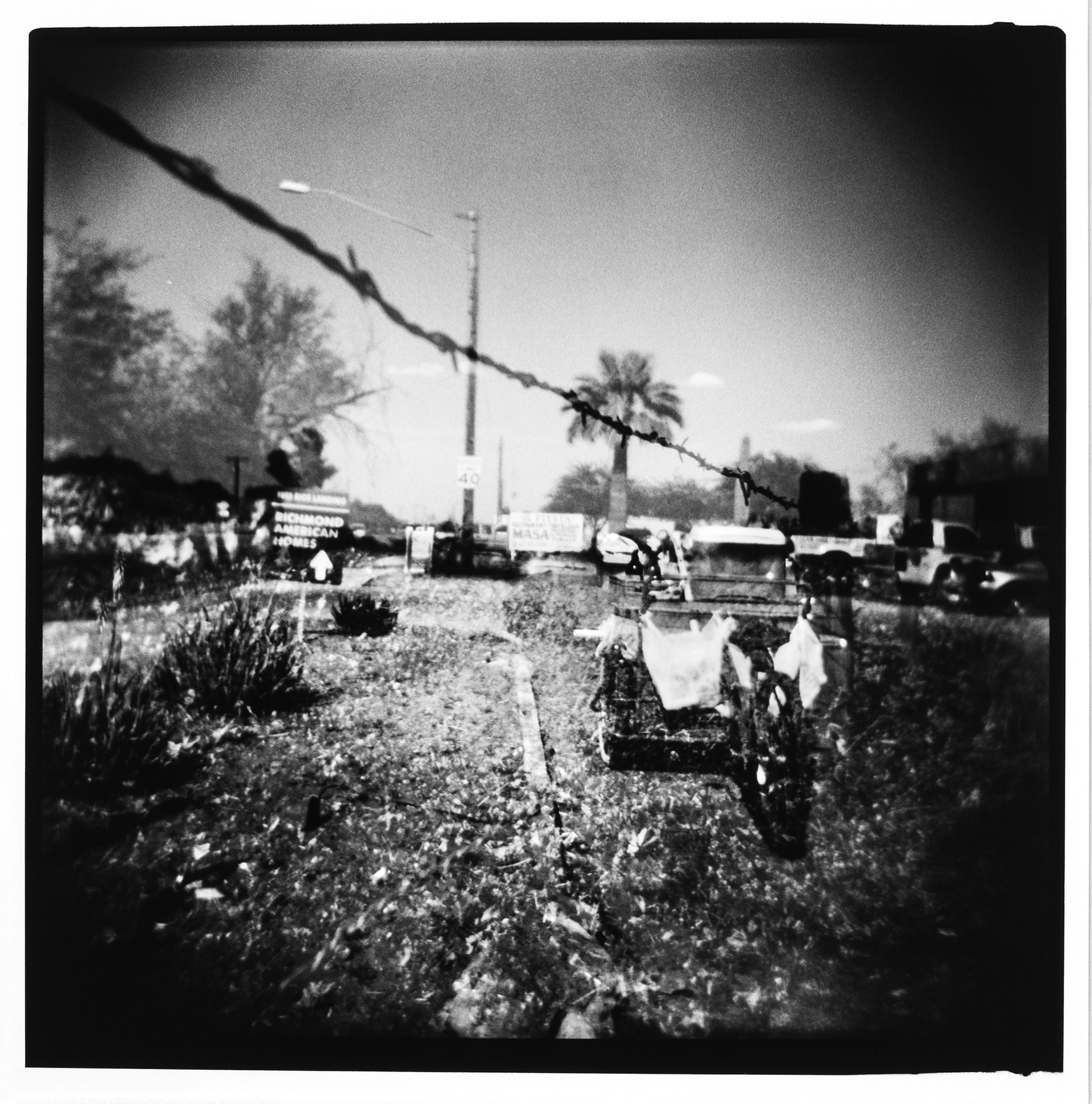

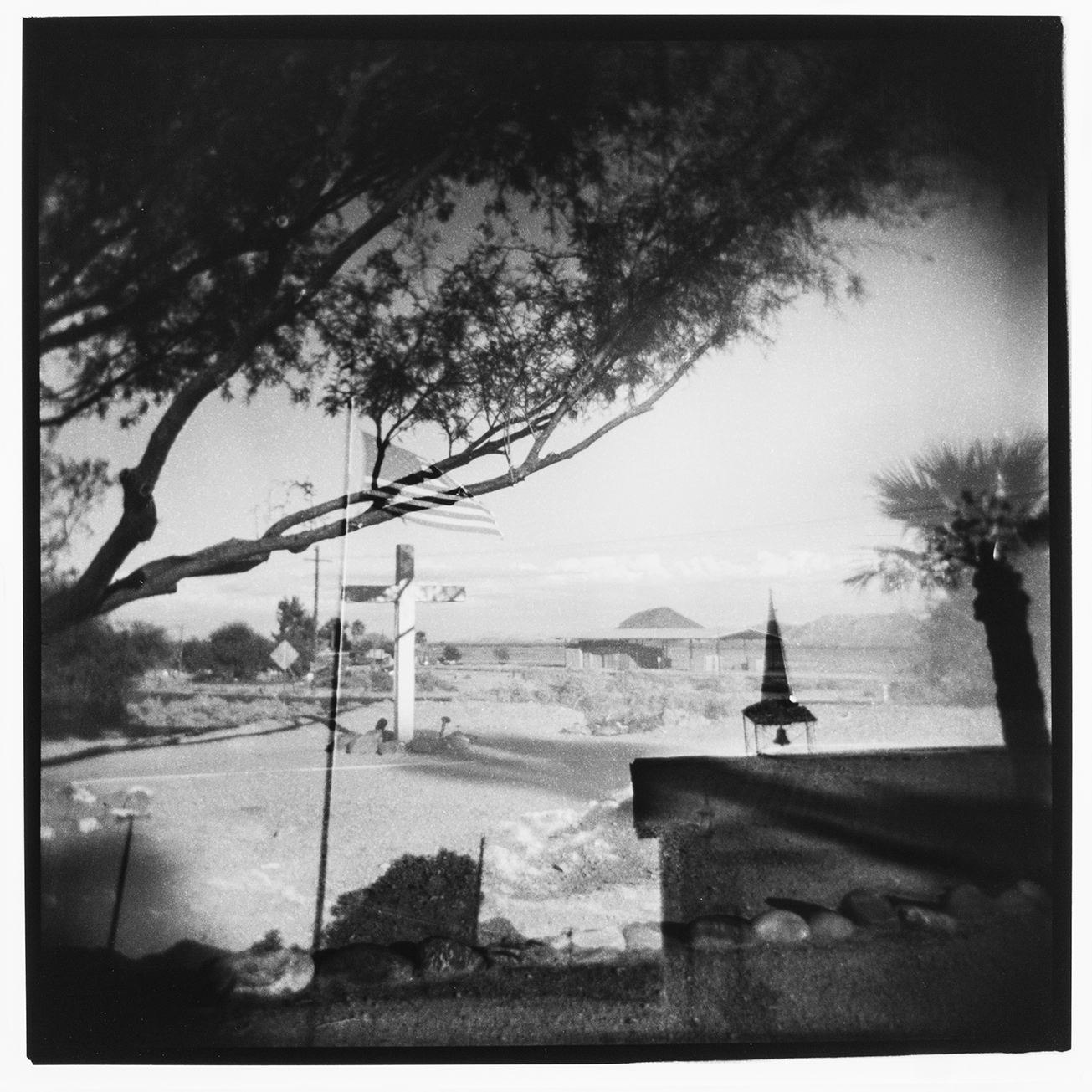

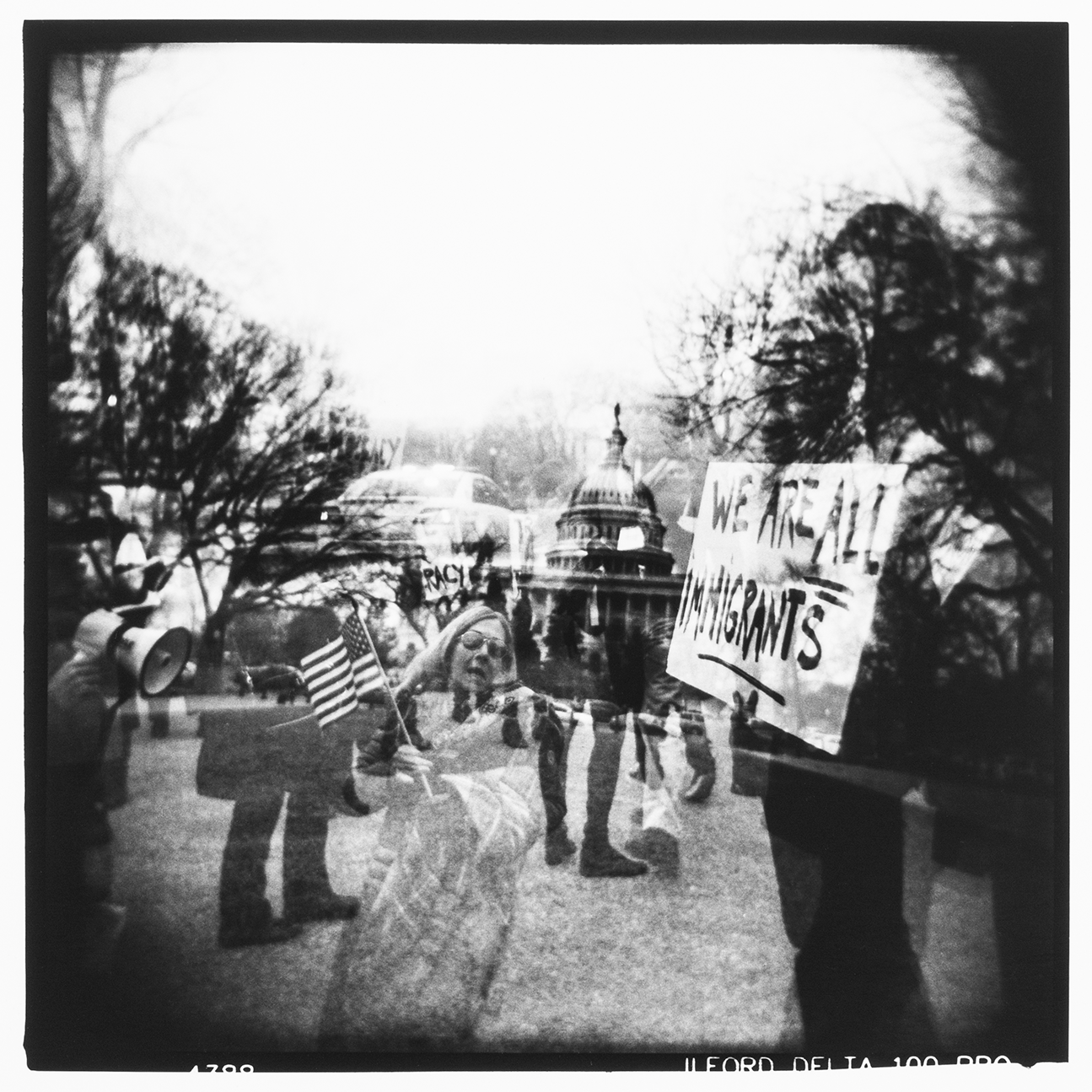

My images capture two different points in time merged through double-exposed photographs. These moments are reflections of memory, the flux of time and the prospect of future. The duality of double-exposures presents the viewer with a sense of past and present, old and new, cultural change, and traversing of borders. The photographs challenge truth, invert spaces, question logic, fuse landscape and people, asking one to carefully examine not just the images, but the issue itself.

Some photographs reveal a child at work, a doorway to an eerie landscape, a people rallying for change. Others use metaphor to tell a story of arduous labor, isolation, and promise. Artifacts in the landscape are symbolic of a people detained, and mimic a plea or a prayer, while the layers evoke slowly dissipating memories of the American Dream.

Ultimately I am part of these people, but aren’t we all. We each have a unique story yet also a shared history. People will continue to make new places their home, be it for political, religious, economic, or personal reasons. The question arises: is our place of origin important, relevant, or forgotten? My photographs don’t necessarily provide the answer but hopefully they further the dialogue.